This dispatch features the books The Great Circle by Maggie Shipstead and Mating by Norman Rush; novels old and new, both examine how women cope with the challenges of being female in a male world.

By Randy Kraft

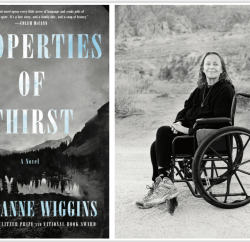

Maggie Shipstead has been nominated for a Booker Award for her third novel, The Great Circle and the book is a great achievement. Spanning a century, and based on the under-glorified women pilots of the early 20th century, including those who flew for the Brits during the war, she goes back and forth in time between one particular pilot, a spitfire of a person who ends up flying spitfires, and the messed up spitfire of an actress who will play her in the biopic. The detail is astonishing. Both orphans, both often looking for love in all the wrong places, you will retrace history, fly into the clouds and be submerged into the shadows of Hollywood filmmaking, and it all feels authentic. A fantastic piece of research as well as writing. My only critique is of the nearly 600 pages, and the descriptions that too often veer into purple prose, at least one character’s story line and likely one hundred pages would not have been missed, then again, it all lines up remarkably well and every moving part has a place. Extremely well done.

Then he said something about how L. A. is dust and exhaust and the hot, dry wind that sets your nerves on edge and pushes fire up the hillsides is ragged lies like tears in the paper that separates us from hell, and it’s towering clouds of smoke, and it’s sunshine that won’t let up and cool ocean fog that gets unrolled t night over the whole basin like a clean white hospital sheet and peeled back again in the morning. It’s a crescent moon in a sky bruised green after the sunset has beaten the shit out of it. It’s a lazy hammock moon rising over power lines, over the skeletal silhouettes of pylons, over shaggy cypress trees and the spiky black lionfish shape of palm-tree crown on too-skinny trunks.

One evening, in the Namib desert, they watched a line of desert elephants, walk along the rim of a sand dune. The animals and the sky behind them were red with dust. Marian found herself relishing the prospect of making camp, having a drink and a fire, going to bed with the man. From the sweetness that ran through her, she knew she had emerged from the war. She wasn’t free of it, but she never would be.

In flying the length of Africa, for instance, we will only cover one track as wide as our wings, glimpse only one set of horizons. Arabia and India and China will pass unseen to the east and the great stretched-out Soviet beast with its European snout and Asian tail. We will see nothing of South America, nothing of Australia or Greenland or Burma or Mongolia, nothing of Mexico or Indonesia. Mostly we will see water, liquid and frozen, because this is most of what there is.

And when you think about houses, really think, aren’t they so weird? They’re boxes where we keep ourselves and our stuff, boxes shaped like Tudor manors and chic cement warlord bunkers like this one and glassy mod spaceships and geodesic domes and sleep vitrines. L.A. is mysterious crumbling old hilltop piles, and it’s haciendas wrapped in bougainvillea and Craftsman bungalows neat as a pin and little flat-roofed things with bars on the windows, and it’s surf shacks and drug shacks and grumpy old man no solicitors shacks and patchouli shacks strung with prayer flags, windows glowing red through printed Indian cotton as thought inside the beating heart of everything.

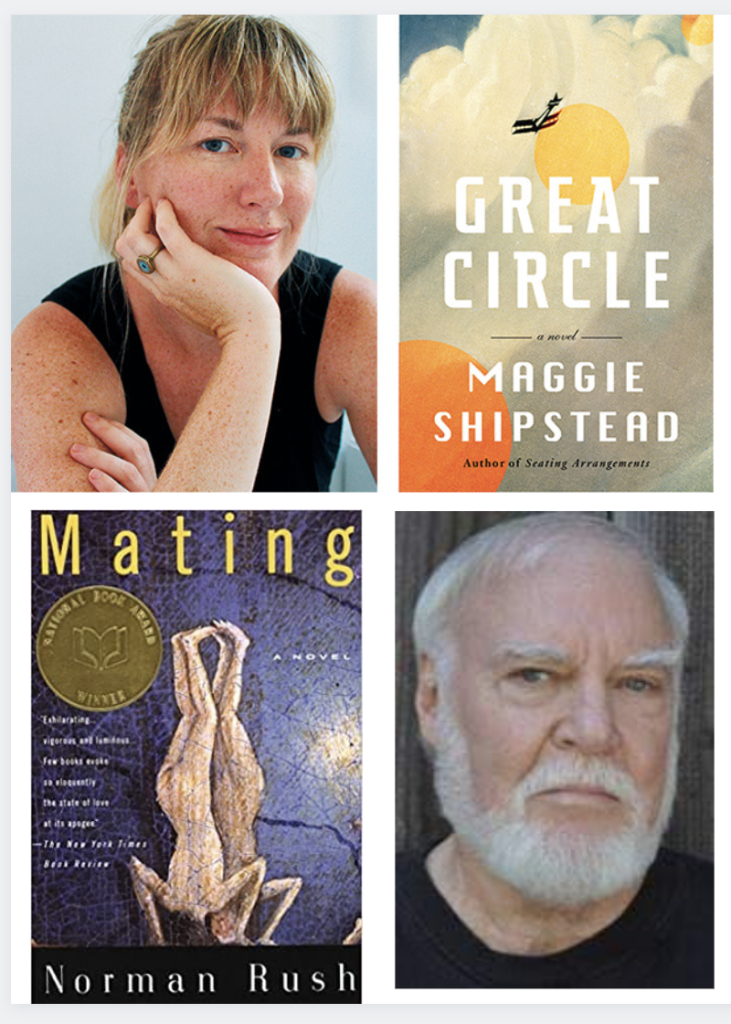

I’ve paired with Norman Rush’s remarkable novel, Mating (a similar page count] which won the National Book Award thirty years ago, and also features an extremely determined spirited female forging a path, literally, into the Botswana jungle, the jungle of academia and ethnographic research and, like Shipstead’s pilot, seeking romance. In this case, looking for love maybe in the wrong place, but off she goes, as if wielding a machete through the dense foliage, to secure her prize. I’ve never read anything like this book. Absolutely mesmerizing, with a plethora of engaging dialogue, with sidebars about who Shakespeare might have been and other intellectual mumbo jumbo which, if you enjoy that sort of thing, is grand. Also one of the hardest novels I’ve ever read — the language incredibly dense and challenging, like the jungle — befitting these complex characters, but often exasperating. This is a novel all highbrow readers should read, for the experience. The chapter titles alone are a treat, and a test of intellect. A tour de force often simply stunning in its observations. Make sure to turn off the phone and block out reading time, it’s impossible to follow otherwise.

My utopia is equal love, equal love between people of equal value, although value is an approximation of the word I want. Why is it so difficult? Assortative mating shows there has to be some drive in nature to bring equals together in the toils of love… I was emotional a lot, privately. I wanted to incorporate everything, understand everything, because time is cruel and nothing stays the same.

These men were not ignorant. The exchange was civil, at first, but very intense and substantive. Harold conceded it was odd that there were not books or papers or any description included among the chattel in Shakespeare’s will, but not that there was anything arresting about references to the circulation of the blood in three of the plays despite Shakespeare having died twelve years before Harvey published his theory…

I was having an overwhelming experience of joyfully being with someone and not wondering what he or I should do next to maintain this. Nobody was entertaining anybody. Remorse is powerful with me, I said. While everyone around here is apologizing, I want to apologize for something myself …

Two extraordinary novels. Two extraordinary women, and the people who pave their journey or throw stones along the way. Among all the excellent fiction out there this year, don’t miss the great stuff that came before. Happy reading.